6.

8. 52. Philippe Marchand (Paris, France) 53. Prof. Dr. Ralph Mayer (Chemnitz, Germany) 54. Gustav Melin (Stockholm, Sweden) 55. Paul Miles (California, USA) 56. Prof. Yasuo Moriyoshi (Chiba, Japan) 57. Dr. Martin Müller (Hamburg, Germany) 58. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Axel Munack (Braunschweig, Germany) 59. Prof. Dr.ir. J.A. Jeroen van Oijen (Eindhoven, Netherlands) 60. Prof. Dr. Ralf Peters (Aachen, Germany) 61. Prof. Dr. Peter E. Pfeffer (Munich, Germany) 62. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Heinz Pitsch (Aachen, Germany) 63. Prof. Jacobo Porteiro (Vigo, Spain) 64. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Ralph Pütz (Landshut, Germany) 65. Prof. Dr. Dr. Dr. h.c. F. J. Radermacher (Ulm, Germany) 66. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Reinhard Rauch (Karlsruhe, Germany) 67. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Hermann Rottengruber (Magdeburg, Germany) 68. Prof. Christine Rouselle (Orleans, France) 69. Alarik Sandrup (Stockholm, Sweden) 70. Dr. habil. Martin Schiemann (Bochum, Germany) 71. Prof. a.D. Dipl.- Ing. Peter Schmid (Esslingen, Germany) 72. Carl-Wilhelm Schultz-Naumann (Munich, Germany) 73. Dr. Irene Schwier (Hamburg, Germany) 74. Prof. Dr.–Ing. Helmut Seifert (Ludwigshafen, Germany) 75. Dr. Kelly Senecal (Wisconsin, USA) 76. Prof. Seong-Young Lee, PhD (Michigan, USA) 77. Prof. Dr. Anika Sievers (Hamburg, Germany) 78. Dipl.-Chem. Anja Singer (Coburg, Germany) 79. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Werner Sitzmann (Hamburg, Germany) 80. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Rainer Stank (Hamburg, Germany) 81. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Michael Sterner (Regensburg, Germany) 82. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Rüdiger C. Tiemann (Saarbrücken, Germany) 83. Prof. Athanasios Tsolakis (Birmingham, United Kingdom) 84. Prof. Sebastian Verhelst (Ghent, Belgium) 85. Dr.-Ing. Jörn Viell (Aachen, Germany) 86. Oldřich Vítek (Prague, Czech Republic) 87. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Holger Watter (Flensburg, Germany) 88. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Thomas Willner (Hamburg, Germany) 89. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Karsten Wittek (Heilbronn, Germany) 90. Dr. Yuri Martin Wright (Zurich, Switzerland) 91. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Kai Wundram (Braunschweig, Germany) 92. Prof. Hua Zhao (London, United Kingdom) 93. Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Lars Zigan (Munich, Germany)

7. Scientists: 1. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Uwe Adler (Erfurt, Germany) 2. Edgar Ahn, PhD (Graz, Austria) 3. Jonas Ammenberg, PhD (Linköping, Sweden) 4. Prof. Dr. José Guilherme Coelho Baêta (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) 5. Dr. R.J.M. Bastiaans (Eindhoven, Netherlands) 6. Dr.-Ing. Bernhard Bäuerle (Stuttgart, Germany) 7. Prof. Dr. Pål Börjesson (Lund, Sweden) 8. Prof. Dr.techn. Christian Beidl (Darmstadt, Germany) 9. Dr.-Ing. Benjamin Böhm (Darmstadt, Germany) 10. Dr. Aleš Bulc (Leipzig, Germany) 11. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Michael Butsch (Constance, Germany) 12. Prof. Ulrich Bruhnke (Lustenau, Austria) 13. Prof. Dr. Matthias Brunner (Saarbrücken, Germany) 14. Prof. David Chiaramonti (Torino, Italy) 15. Dr. Klaus Dieterich (Stuttgart, Germany) 16. Prof. Dr. Friedrich Dinkelacker (Hannover, Germany) 17. Prof. Dr. habil. Andreas Dreizler (Darmstadt, Germany) 18. Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Eberhard R. Drechsel (Munich, Germany) 19. Prof. Dr. Alexander Eisenkopf (Friedrichshafen, Germany) 20. Prof. Mats Eklund (Linköping, Sweden) 21. Prof. Alessio Frassoldati (Milano, Italy) 22. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Thomas Gänsicke (Wolfsburg, Germany) 23. Dr.-Ing. Claus-Eric Gärtner (Munich, Germany) 24. Prof. Dr. techn. Dipl.-Ing. Bernhard Geringer (Vienna, Austria) 25. Bernhard Gerster (Basel, Switzerland) 26. Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Jörn Getzlaff (Zwickau, Germany) 27. Prof. Dr. Hartmut Gnuschke (Coburg, Germany) 28. Dr. Armin Günther (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) 29. Marcus Gustafsson (Linköping, Sweden) 30. Prof. Ernst-M. Hackbarth (Munich, Germany) 31. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Karl-Ludwig Haken (Esslingen, Germany) 32. Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Kay-Rüdiger Harms (Wolfsburg, Germany) 33. Prof. Dr. Stefan Hausberger (Graz, Austria) 34. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter Heidrich (Kaiserslautern, Germany) 35. Dr. Paul Hellier (London, United Kingdom) 36. Dr. Jose Martin Herreros (Birmingham, United Kingdom) 37. Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerhard Hettich (Stuttgart, Germany) 38. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Karl Alexander Heufer (Aachen, Germany) 39. Dr. Axel Ingendoh (Odenthal, Germany) 40. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. h.c. Rolf Isermann (Darmstadt, Germany) 41. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Markus Jakob (Coburg, Germany) 42. Jean-Marc Jossart (Brussels, Belgium) 43. Prof. Sanghoon Kook (Sydney, Australia) 44. Prof. Dr.-Ing. André Casal Kulzer (Stuttgart, Germany) 45. Prof. Dr. Thomas Lauer (Vienna, Austria) 46. Dr. Felix Leach (Oxford, United Kingdom) 47. Prof. Francisco Lemos (Lisbon, Portugal) 48. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Frank Atzler (Dresden, Germany) 49. Dr. Klaus Lucka (Aachen, Germany) 50. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Bernd Lichte (Wolfsburg, Germany) 51. Prof. Ing. Jan Macek, DrSc., FEng (Prague, Czech Republic)

1. Nº 7.23 Madrid, 7 de febrero de 2023 CARTA ABIERTA UE RECONOCIMIENTO POTENCIAL ECOCOMBUSTIBLES

11. 3 IRU is the world road transport organisation and the voice of one million transport operators in the European Union, connecting societies with safe, efficient and green mobilit y and logistics. FuelsEurope represents with the EU institutions the interest of companies m anufacturing and distributing liquid fuels and products for mobility, energy & feedstocks for industrial value chains in the EU. European Shippers’ Council was founded in 1963 to represent the logistic interests of ma nufacturers, retailers, and wholesalers, collectively referred to as shippers, in all mo des of transport. ESC members are national shippers’ councils, key European commodity trade associations, and corpora te members.

5. Open letter Joint statement of the EU industry: CO₂ Regulation for Heavy-Duty Vehicles should recognise decarbonisation potential of sustainable and renewable fuels As European industry, including fuel and automotive suppliers, vehicle manufacturers, dealers, repairers and transport operators we eagerly anticipate the European Commission proposal on the revision of the CO₂ Regulation for Heavy-Duty Vehicles (HDVs). Heavy-Duty transport is a vital sector for the functioning of the internal market and a suitable regulatory framework shall support the development of clean vehicles using different technologies and fuels. Decarbonisation is an immediate challenge and all options that can have a rapid impact need to be enabled. Sustainable and renewable fuels can speed up the process and contribute to achievement of the “Fit for 55” and the full decarbonisation targets in road transport. The signatories of this letter welcome the revision of the CO₂ standards for HDVs in line with the “Fit for 55” objectives and believe that a recognition of all CO₂ emission reduction pathways along the entire value chain is critical. Transport operators and vehicle manufacturers must be encouraged to consider cleaner fuel alternatives to fossil fuels, immediately available today, including liquid and gaseous renewable and synthetic fuels. Depending on use cases, technology diversity is needed where all technologies, including electrification/hybridisation, hydrogen and sustainable and renewable fuels can play a role. The undersigned organisations recommend that sustainable and renewable fuels are considered for compliance in the CO₂ Regulation for HDVs. Including such a provision in the Regulation would support the EU’s Green Deal objectives and accelerate the decarbonisation of the commercial transport sector. Signatories:

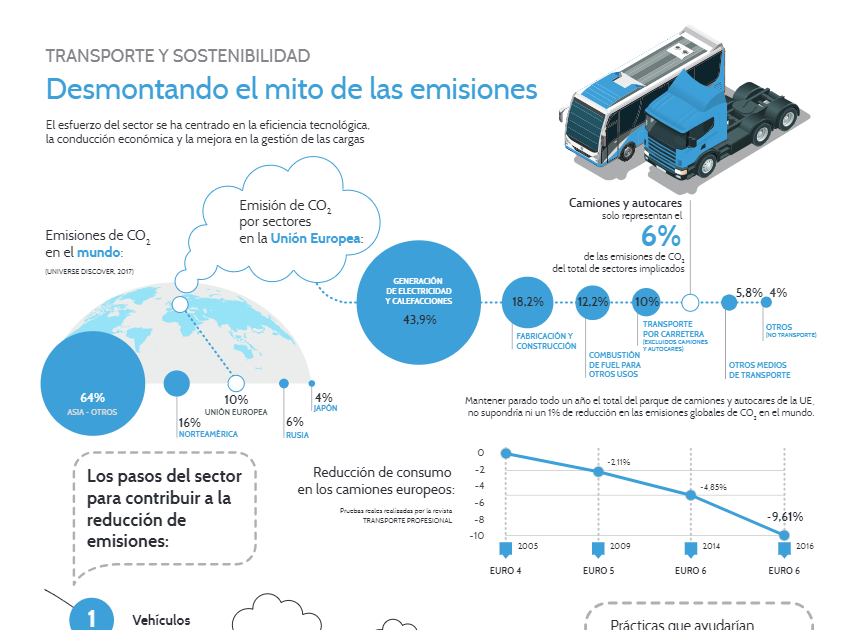

2. Nº 7.23 Madrid, 7 de febrero de 2023 CARTA ABIERTA UE RE CO NOCIMIENTO POTENCIAL ECOCOMBUSTIBLES Como es bien sabido, la presión de muchos gobiernos de diverso alcance (municipal y regional, hasta continental, pasando por los gobiernos de la mayoría de los Estados de la Unión Europea) hacia la solución “eléctrica” para el transporte no cesa de incrementarse. En muchos casos la actuación política deja de lado la “neutralidad tecnológica” y está considerando dichos vehículos equipados con baterías casi como la única vía disponible para cumplir los compromisos de neutralidad en emisiones de CO2 que la UE estableció para el 2050. Más allá de las posibilidades reales que hoy por hoy podamos estimar que tiene ese tipo de tecnología en el campo de los camiones pesados de media y larga distancia, creemos que es necesario que se tengan en cuenta otras posibles alternativas y que los líderes políticos sean conscientes de que no es ni aconsejable ni justo apartarlas a la hora de establecer incentivos, esquemas fiscales o ayudas a las diferentes industrias. Una de las alternativas que, en opinión de esta asociación, cuenta con mayores ventajas en cuanto a rapidez de implantación y menores barreras de desarrollo son los llamados ecocombustibles. Estos, tanto líquidos como gaseosos, son molecularmente equivalentes a los que actualmente utilizan nuestros camiones, pero, por su origen sintético o biológico, su combustión no incrementa en absoluto los niveles de CO2 presentes en la atmósfera. De hecho, ASTIC es una de las organizaciones fundadoras en España de la Plataforma para la promoción de los ecocombustibles, de la que ya

3. hemos tenido otras ocasiones de comentar anteriormente. En este orden de cosas, me complace comunicarle que ASTIC ha firmado una carta abierta que se adjunta - más abajo puede ver su versión en español- juntamente con numerosas corporaciones y organizaciones de la industria, entre ellas algún miembro de ASTIC como es Transportes Monfort, que ha sido enviada a la presidenta de la Comisión, Ursula von der Leyen, y a varios comisarios ( Timmermanns, V ă lean, Breton y Schmit ) cuyas competencias tienen relación directa con el asunto. Tratamos así de involucrar a más y más protagonistas del sector en este debate, ya que esto tendrá un gran impacto en el futuro de la sostenibilidad ambiental, económica y social, así como en la eficiencia del transporte por carretera. Por otro lado, y en el mismo sentido, desde nuestra organización internacional, IRU, concretamente desde su delegación en Bruselas, se ha hecho lo propio en colaboración con representantes de cargadores europeos (ESC) y el homólogo europeo a nuestra Plataforma, llamado “Fuels Europe”. Puede tamb ién encontrar copia de esta carta en archivo adjunto. TRADUCCIÓN CARTA AOP: Declaración conjunta de la industria de la UE: la regulación de CO ₂ para vehículos pesados debe reconocer potencial de descarbonización de los combustibles sostenibles y renovables Dado que la industria europea, incluidos los proveedores de combustible y automoción, los fabricantes de vehículos, los concesionarios, reparadores y transportistas esperamos con impaciencia la propuesta de la Comisión Europea sobre la revisión del Reglamento de CO ₂ para vehículos pesados (HDV). El transporte pesado es vital , sector para el funcionamiento del mercado interior y un marco reglamentario adecuado apoyarán el desarrollo de vehículos limpios utilizando diferentes tecnologías y combustibles. La descarbonización es un desafío inmediato y todas las opciones que pueden tener un impacto rápido deben estar habilitadas.

4. Los combustibles sostenibles y renovables pueden acelerar el proceso y contribuir al logro de l “Fit for 55” y los objetivos de descarbonización total en el transporte por carretera. Los firmantes de esta carta dan la bienvenida a la revisión de los estándares de CO ₂ para vehículos pesados en línea con los objetivos "Fit for 55" y creemos que un reconocimiento de todas las vías de reducción de emisiones de CO ₂ a lo largo de toda la cadena de valor es fundamental. Los operadores de transporte y los fabricantes de vehículos deben estar alentados a considerar alternativas de combustible más limpias a los combustibles fósiles, disponibles de inmediato hoy, incluyendo combustibles renovables y sintéticos líquidos y gaseosos. Dependiendo de los casos de uso, la tecnología necesita diversidad donde todas las tecnologías, incluyendo la electrificación/hibridación, hidrógeno y los combustibles sostenibles y renovables pueden desempeñar un papel. Las organizaciones abajo firmantes recomiendan que se consideren los combustibles sostenibles y renovables para cumplir con el Reglamento de CO ₂ para vehículos pesados. La inclusión de una disposición de este tipo en el Reglamento es apoyar los objetivos del Pacto Verde de la UE y acelerar la descarbonización del sector comercial , sector del transporte. C/ Príncipe de Vergara, 74, 3 planta - 28006 MADRID Tlf.: 91 451 48 01 / 07 – Fax: 91 395 28 23 E-mail: astic@astic.net Nota: Prohibida la edición, distribución y puesta en red, total o parcial, de esta información si n l a autorización de A ST IC

9. Frans Timmermans Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal European Commission Rue de la Loi 200 / Wetstraat 200 1040 Brussels Belgium By email BR 1059007/SMR Brussels , 1 February 2023 Re: Call for preserving essential technology options to move logistics chains Dear Vice-President Timmermans, The undersigned, IRU, ESC and Fuels Europe, representing road transport operators, ship pers and energy suppliers, are strongly committed to contribute to the decarbonisation of the E U ’s transport industry . Our sectors support the objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 and stand ready to contribute to the regulatory framework to achieve this objective. However, the attainment of the carbon neutrality goal will very much depend on the techno logy options allowed by the upcoming legislation. Logistics chains should not be subject to an experiment which could jeopardise the stability of supply: the EU should recognise carbon neutral fuels in the upcoming CO2 standards for heavy-duty vehicles ( HDV ) as a long-term solution for sustainable road transport alongside electrification and hydrogen. Combustion and current fuels Today, liquid fuels provide energy security for highly resilient and flexible HDV transport and logistics chains. This has proven to be critical for the efficient operation of the singl e market, including for emergency responses to crises of all types. Today, the vast majority1 of trucks sold have an internal combustion engine using liquid fuel. Out of the total fleet of over 6 million HDVs used to transport goods in the EU, about 2 million vehicles are used in the long-haul transport of goods. With these vehicles, transport operators and drivers ensure the security of vital supplies across the EU, including on major South-North and E ast-West food corridors. Most of these vehicles weigh 40 tonnes or more. In the Nordic countries, loaded vehicl es can reach up to 76 ton ne s. Electric batteries and hydrogen fuel cells There is no doubt that European truck manufacturers will make great progress in develop ing new electrification and hydrogen technologies, enabling a wide offering of new alternatives for operators. However, completely switching from the 1,500km driving autonomy of a liquid fuel 40-tonne truck to an electric truck’s autonomy of 300km, with uncertain charging infrastructure and grid availability, will pose serious risks, at the very least on some long-haul routes. The electric power required to recharge a single large truck’s battery is equivalent to the daily electricity ne eded to power more than 100 households. 1 Fuel types of new trucks: diesel 95.8%, electric 0.5%, alternative fu els 3.6% share full-year 2021 - ACEA - European Automobile Manufacturers' Association (ref. 2021)

10. 2 Hydrogen should also be an option, but it has limitations and cannot alone be a complete substitute. F or example, a thorough risk analysis is needed regarding the potential use of hydroge n vehicles for the transport of dangerous goods. Equally, many ferry companies currently prohibit the boardi ng of electric and hydrogen vehicles for safety reasons, which is a major issue for island Member S tates. Furthermore, resourcing green hydrogen for a huge truck fleet may pose serious practical difficulties. Therefore, a proposal for Europe’s logistics sector that moves completely away from combustion can only be described as an experiment with unnecessary risks. Carbon neutral fuels Liquid fuels of non-fossil origin are progressively replacing fossil fuels. Whether they come from biomass (biofuels) or a combination of recycled CO2 and clean hydrogen, such alternative fuels have one essential property in common: when burned, they release only the same amount of CO2 which was originally absorbed from the atmosphere. In other words, they do not increase the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere and can therefore be labelled “carbon neutral fuels”. It is clear that, in a we ll - to -wheel approach, some CO2 is released during the production phase of these fuels, but the sa me can be said for electricity and hydrogen. However, under a “tailpipe” regulation model like the HDV CO2 standards, releasing recycled CO2 or releasing no CO2 at all needs to be considered as “neutral” for the climate (unlike fossil fuels that release linear CO2). Carbon neutral fuels are also the most realistic option to decarbonise aviation, m ost maritime transport and the existing fleet of road vehicles. The availability of sustainable bioma ss is more than sufficient to satisfy the demand in advanced biofuels for the three transport modes2. To quick ly scale up the production of carbon neutral fuels, it is essential that investors can build their busi ness case assuming that these fuels will first mainly satisfy demand in road transport, and then progressively move on to aviation and maritime. Today, there are 124,000 liquid fuelling stations across the EU, each one with multi ple pumps. They will all be capable of delivering 100% renewable fuels when production is scaled up. In terms of infrastructure, this is highly cost effective. Finally, the combustion of H2 in internal combustion engine vehicles should al so not be arbitrarily excluded, as their CO2 emissions from vehicles are negligible. Call for options and safe choices Considering the arguments above, IRU, ESC and Fuels Europe call for the full and equal recognition of carbon neutral fuels and hydrogen combustion in HDV CO2 regulation, as viable lon g-term solutions alongside electrification and H2 Fuel Cells. For a well-functioning and stable EU logistics sector, we urge the EU to allow logistics chains to decide which technology is th e most suitable for their various types of operations to achieve our common goal, which is carb on neutrality. Raluca Marian General Delegate of IRU to the EU Godfried Smit Secretary General European Shippers’ Council John Cooper Director General Fuels Europe 2 Sustainable Biomass Availability in the EU, to 2050 - Imperial Colle ge London Consultants for Concawe